Orfeo, crossing the Ganges

September 2013Copyright © 2013 CBH

Orfeo, crossing the GangesSeptember 2013Copyright © 2013 CBH |

NEEMRANA MUSIC FOUNDATION |

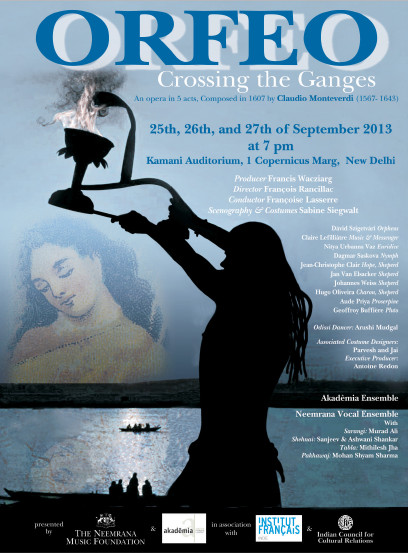

| Orfeo publicity postcard |

NASA VISIBLE EARTH |

Indian traditions—including their music—being so very strong, our own classical music has never made much headway despite Western influence in the subcontinent for several centuries. While there are two symphony orchestras (Symphony Orchestra of India in Mumbai & Indian Philharmonic Orchestra in Bangalore), performances are relatively rare and there are few possibilities in the country for advanced study in Western music. My sole Indian experience had been a brief visit to Mumbai in 1999, so I was excited to be invited to assist a cross-cultural project conceived by Françoise Lasserre with her French group Akadêmia to bring Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo to Delhi in 2013.

Orfeo, crossing the Ganges was to be relevant to an Indian audience. Françoise described the starting point of the project in her program notes:

“Beyond the myth of Orpheus, we imagine a young man from a Western country, proud of his talent for singing, who kidnaps a revered Indian dancer, driven by the violence of love at first sight. To experience his love, he violates all the rules of Indian society. The great Shiva takes revenge by killing the beautiful woman whose purity has been compromised. Driven by the heroism of blind love, Orpheus sets off to India to search for her. Acknowledging all the skills he displays, the God seems to take pity on him and agrees to give the young dancer back. Yet it is but an illusory shadow that follows Orpheus, for it seems that the latter’s heart lacks the purity to be worthy of such a benediction.”

After more than eighteen months in the planning, I spent all of September 2013 in India for the complete production rehearsals in the lead-up to three performances in the 632-seat Kamani Auditorium in Central Delhi. (A final performance followed a week later at Cité de la Musique in Paris, but I was already back in Australia working with Andreas Scholl and the Australian Chamber Orchestra.)

CAREY BEEBE |

| Pentagonal virginal by Patrick Chevalier c1990 |

Monteverdi was very specific in his instrumental requirements for L’Orfeo. In terms of keyboards, he wanted two harpsichords, two organs with wooden pipes, and a regal. Sadly, few productions can run to this anywhere in the world today, and it would not be possible for India. The continuo organ flew from Sydney, and my suggestion was enthusiastically taken up that we consider the substitution of a locally-found Indian harmonium for Monteverdi’s snarly-sounding regal.

This was the first time I had worked with French early keyboardist Laurent Stewart, who has collaborated with Françoise and Akadêmia for more than twenty-four years. For plucked keyboard, Laurent borrowed a real quill Italian-style pentagonal virginal built by Patrick Chevalier c1990. He traveled with this compact instrument from Lyon, and for convenience we put it on top of the organ once rehearsals were underway.

The virginal was well made and in good structural condition but it appeared not to have had much maintenance in a considerable time. Both it and the harmonium required some work to bring them up to what I considered performance standard: It’s always my aim to return borrowed instruments to their owners in better condition than they came!

For the first two weeks of intensive rehearsals for the singers with Laurent on keyboards and Thomas Dunford on archlute, we were cloistered in an early 19th-century hilltop fort-palace near Tijara, three or four hours by road south of Delhi. Not even appearing on the Lonely Planet radar, I knew we were at a real destination. The hill had been secured on a sixty-year lease by the Neemrana Group a decade previously, and they were in the slow process of turning the ruins into one of their luxury “non-hotels” for which they have become famous throughout India. (The Neemrana Music Foundation were the generous principal sponsors of Orfeo, and we were part of their probably most ambitious performance project to date.) It must be at least another two years’ work before the Tijara complex could be considered ready for paid guests, but we felt enormously privileged to be able to share this historic location and be accommodated and waited upon hand and foot for three superb meals a day and more in the mostly-complete Maharani’s building.

The splendid surroundings of rural Rajasthan eclipsed most of our shared discomfort at fickle internet and lack of continuous electricity supply. We were beyond the limit of 3G cellular phone service, with even Edge dropping back to 2G or long periods entirely without signal. Some of the European singers were not that keen on sharing their rooms with the local geckos (Hemidactylus flaviviridis)—until they realized the usefulness of those sticky-footed lizards in keeping the insect population under control. At such high temperatures this time of year, if we had water in the pool, it would have been paradise.

CAREY BEEBE |

| 270° View of rural Rajasthan from my cupola-covered balcony on the NE corner of the Maharani’s building, Tijara Fort-Palace |

Our days at Tijara began with breakfast, then the singers stretched in the Pavilion of the Four Winds (right in the above photo), so-named because its exposed position is guaranteed to capture any available cooling breeze. This was where the Maharajah would have greeted visiting emissaries—had he lived long enough to see his dreams realized and moved in. Meanwhile, I tuned organ and virginal for the late morning music rehearsal back in a ground-floor room in the Maharani’s building. Following lunch, we would adjourn outdoors to do the afternoon stage rehearsals on a first-floor terrace. Although shaded by this time of day, I had to keep the keyboards in acceptable tune for five hours at 34°C. A late dinner followed, and we retired exhausted, knowing that the following day would bring pretty much the same.

CAREY BEEBE |

| Moving the organ in Tijara—Indian style. |

I would have liked to have had a simple trolley to be able to easily move the organ around myself, but my request sent with a picture some months previous had fallen on deaf ears: When I followed up a few days prior to my departure from Sydney, I was told there is no such thing in India, and we would use four men. And so we did.

The two weeks flew and it was soon time enough to return to Delhi, meet the orchestral musicians who had flown in from Europe with their instruments, and move into the performance venue. We had theorbo doubling on guitar, triple harp, lirone, two bass viols and one tenor, two violins, two cornetti doubling on recorders, and percussion. With keyboards and archlute, all thirteen players had to fit into the rather narrow orchestra pit in front of the Kamani Auditorium stage. Rehearsal conditions were difficult in the Delhi heat, as the hall management wanted to avoid the expense of running the air conditioning except during the performances. Many gut strings were broken before some pedestal fans were brought in to alleviate excessive perspiration.

The French Accor hotel group were among our other valued sponsors, and we were to be lodged at their brand new Ibis at Delhi Airport. While this hotel was complete and staffed, it had not yet been approved for occupancy. Instead, we were grateful to be fed and accommodated at the Ibis in Gurgaon, a new satellite city of Delhi. Although only some 34km distant from the hall, with the diabolical traffic including cattle, pigs, donkeys, bicycles, autorickshaws and buses all jostling to share the parlous state of the roads, our hotel was usually an hour and half drive day or night. We didn’t have a day off, running right into the General Rehearsal and three performances.

One day I was, however, able to visit the musical instrument museum of the nearby Sangeet Natak Akademi (संगीत नाटक अकादेमी). I unexpectedly discovered a 1960s Wittmayer harpsichord there, donated some years ago by the German Embassy but sadly now completely unplayable with numerous broken strings and decayed leather plectra. This instrument did, however, bring to three the total number of early keyboards I know of in this entire country of a staggering 1.21 billion people. Another day I visited the large Sharan Rani Bakliwal Collection of Musical Instruments in the National Museum (राष्ट्रीय संग्रहालय), although there is little mention of the collection on their otherwise comprehensive website. (A report on the significance of that collection can be better found in an article in The Economic Times from early 2011 titled “Sharan Rani Bakliwal and her devotion to music”.)

CAREY BEEBE |

Some of the Indian musicians on stage, opening Act III: Mithilesh Jha tabla; Murad Ali sārangī; Ghulam Ali & Shiraz Ahmed tanpura; |

Instead of Monteverdi’s opening, Orfeo, crossing the Ganges began with a special locally-composed prelude by Madhup Mudgal featuring his daughter, Odissi dancer Arushi. Indian musicians took part in an onstage band, using the short-necked bowed string sārangī (सारंगी), the long-necked unfretted lute tanpura (तानपूरा), the quadruple reed conical bore shehnai (शहनाई), the pair of hand-drums tabla (तबला), and the elongated, two-headed drum pakhawaj (पखावज). They returned—minus the shehnai—to open Act III, and also at the end.

Performance pitch of the show was to be A466, and temperament Quarter-comma meantone—both very appropriate for Monteverdi. Some compromizes had to be made. The Indian instruments were unable to be played above A460, so they dictated the pitch of the whole ensemble. While my Klop organ transposes to A466, a few of the bass pipes did not have sufficient length to be tuned down to A460, but this lower pitch could be accomplished by shading a few of the pipe mouths with pieces of taped card.

The pentagonal virginal lacked a transposing keyboard, and we were reluctant to pull the mostly twenty-five year old brass strings a tone higher than usual. (I would have liked to have restrung the entire instrument, in any case.) Instead, Laurent played both organ and virginal at A415 from a transposed score. I set b' on both instruments to 460Hz and transposed the temperament a tone accordingly so that the wolf was between A♯–F instead of the usual G♯–E♭. The existing pitch (about A458) and quasi-Equal Temperament of the borrowed Indian harmonium with its two sets of reeds was not to be so easily changed and then reverted after the show, but in practice proved not to be any problem because of its specific and limited use in Act III—only accompanying Caronte, the river Styx (here, the Ganges) boatman to the Underworld.

I never cease to be amazed how the many complexities are overcome and somehow everything comes together in time for opening night—but then, that’s a good part of the magic of Opera.

We knew we would have a free day after the last Delhi performance, so a decision was made to charter a bus to take most of us to Agra to visit the Fort and the Taj Mahal. On Sunday September 29, it was time to farewell India, the company traveling to Europe and regrouping in Paris for the final performance on October 5, while I returned to Sydney.

Many friends were made, and we look forward to the opportunity to work together again—if not India, then somewhere else.

CAREY BEEBE |

| Taj Mahal, Agra |

| Projects index | |

| Site overview | |

| Harpsichords Australia Home Page |