Press GalleryCopyright © 2004 CBH & individual authors & photographers |

People either love or hate harpsichords. Those in favour of the instrument are fanatical devotees; others have described the sound emitted from these early keyboard instruments as “a performance on a birdcage with a toasting fork”.

Whatever you may think of the audio qualities of the keyboard, there is no denying they are elegant instruments to view, especially those decorated by Moss Vale resident Diana Ford.

Diana

didn’t develop her passion for harpsichords until she was in her 20s,

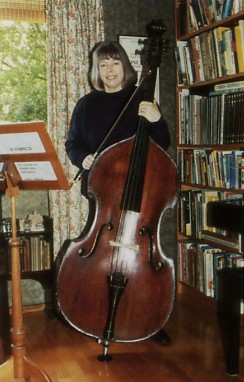

despite a lifetime of music and art. “I took up the double bass at 14,

after years of playing the piano. The school violin teacher offered four free

lessons if I would play the double bass in the school musical Merrie England in

two weeks time. I agreed and the bass was pulled out from among the broken chairs

under the stage, all dusty and neglected, but after those four lessons and performing

some right, but mostly wrong, notes in the production, I never looked back.”

Diana

didn’t develop her passion for harpsichords until she was in her 20s,

despite a lifetime of music and art. “I took up the double bass at 14,

after years of playing the piano. The school violin teacher offered four free

lessons if I would play the double bass in the school musical Merrie England in

two weeks time. I agreed and the bass was pulled out from among the broken chairs

under the stage, all dusty and neglected, but after those four lessons and performing

some right, but mostly wrong, notes in the production, I never looked back.”

After school Diana developed her talent for art, training as a graphic artist at the National Art School by day, and maintaining her love of music by attending the Conservatorium of Music at night, in order to play the bass in the Australian Youth Orchestra.

She then travelled to England and worked as a graphic artist alongside husband Cam, who was an Australian animator on the Beatles’ movie Yellow Submarine. “With all the travelling and having children in my 20s, I didn’t really have time to play anything for about 1- years, except the odd casual spot in an orchestra.”

Her interest was stirred again about 25 years ago when she bought a double bass and joined Willoughby Symphony Orchestra. Thus began a long association with many orchestras.

In the late 80s a friend who ran The Bass Shop in Sydney rang to tell her he had found her a student for the double bass. “I said I wasn’t ready for that — after all I had been an art teacher, not a music teacher —but my friend wouldn’t let me get out of it.” By the time she left Sydney a year ago, she had taught more than 200 private students. A few still travel to Moss Vale every couple of weeks for lessons, and she has picked up new students in the region, including some from the Wollongong Conservatorium.

“I love teaching, and I love kids … I don’t think I could survive without them — they have been wonderful,” she says.

Diana also plays the viola da gamba, an early English instrument that looks like a very small double bass, but with gut instead of metal strings. “These instruments are more manageable. When I’m extremely old I’ll probably end up playing the treble viola da gamba.” laughs Diana. She does not teach this instrument, reserving it purely for enjoyment, including playing with friends and small groups of like minded musicians.

“There is a whole separate repertoire for these instruments,” she says. “A group of players is called a consort, and they attract a wide variety of people. It’s a bit like people who are interested in harpsichords — they tend to be quite different from mainstream musicians.”

The

harpsichord, another of Diana’s passions, is one of the first things you

notice when entering her house. Her interest in them started early — she

recalls attending a recital in London in the 60s and being carried away by the

sound — but it wasn’t until the early 80s, when she met harpsichord

maker and musician Carey Beebe, that she became hands-on with the instrument.

She has since painted around 15 instruments crafted by Beebe.

The

harpsichord, another of Diana’s passions, is one of the first things you

notice when entering her house. Her interest in them started early — she

recalls attending a recital in London in the 60s and being carried away by the

sound — but it wasn’t until the early 80s, when she met harpsichord

maker and musician Carey Beebe, that she became hands-on with the instrument.

She has since painted around 15 instruments crafted by Beebe.

Despite their appearance, the harpsichord is only similar to a piano in that it has a keyboard. The sound comes from plucking the strings, as opposed to hitting them with a hammer as in a piano. They need to be tuned constantly, and are versatile in that they can tune in different temperaments (the relationship of one note to another). With a piano, every note is an even tone away from the next; however with a harpsichord you can adjust the tuning to accommodate different styles of music.

Another difference is that with a harpsichord you cannot control the volume, whereas with a piano you can hit the keys gently or strongly and gain extra control with the pedals. This is one of the reasons the instrument gave way to the piano in the late 1800s [sic]; the piano was more suited to large rooms and playing to crowds of people.

The type of harpsichords that Diana decorates are crafted in the traditional style originating from Antwerp in the 1500s, and the Ruckers family. However, she also follows the French style of art for the instrument developed in the 1600s [sic] by a maker called Taskin. She paints the soundboard of the harpsichord, which is the expanse of wood beneath the strings.

Her designs are depictions of flora and fruit. “People didn’t have flower gardens in those days — gardens were for eating or medicinal purposes. Many of the flowers in Europe came from the Middle East or Asia. That is why flowers were used so much in decorations.” She says the Flemish style is more a design than a visual representation, while the later French artwork is more naturalistic.

Her main inspiration comes from her own abundant garden — tulips, roses, lilies, irises — however she would love to paint a harpsichord in Australian native flowers. Traditionally, the designs also feature a bird, and various moths and beetles; indeed Diana’s signature is a ladybird. “I painted an instrument for one lady who hated insects and wouldn’t allow the usual adornments, but I still managed to get my ladybird there, half-hidden under a leaf.

I’m so lucky because decorating harpsichords ties in beautifully with my love for art and flowers.”

She is faithful to the original paints and designs, and is thus restricted to a limited palette of about nine colors. For example, the blue paint is cobalt pigment mixed with gum arabic, a thick substance that results in a relief style effect. “All the designs are done with watercolor, without any varnish over the top. The beauty of it is when a layer of dust settles on it, the colours become muted and that is part of the charm. But it also makes them very vulnerable — keep drinks well away!”

Diana

estimates she spends around 60 hours for each work and Beebe sells the finished

harpsichords for anything between $30,000 and $80,000.

Diana

estimates she spends around 60 hours for each work and Beebe sells the finished

harpsichords for anything between $30,000 and $80,000.

The artist’s own harpsichord, a variety known as a spinet, is conspicuously unpainted. “They were plain because they were in everyday use — in the same vein as a cottage piano. Having said that though, Handel composed on an instrument exactly the same as mine.”

The distinctive sound is the main element that attracts Diana to this instrument, and the fact that it is so closely associated with early music. “I have played masses of Romantic and Modern music in orchestras for a long time, but the early music associated with the harpsichord is a very personal sort of music.

“It is delicate — made for the home and small churches and salons of the day. It is wonderful that two friends can sit down with a couple of viols and play beautiful music, then someone else can join them on a harpsichord and you have a fantastic evening’s entertainment in your own home,” she says.

Diana’s harpsichord and piano are kept company by a total of seven double basses, in addition to her viols. “The double bass started it all for me. It introduced me to orchestras and teaching music. It is a versatile instrument — it can be played in anything from chamber music to jazz.” She has her own 100-year-old bass, a half-size and a quarter size, a couple of one eighth size, and the only one tenth size double bass in the country, brought in from New York, which is perfect for an eight-year-old.

Double bass players are not as common as violin players, mainly because of the price of the instrument and also because they are difficult to move around. “I have known someone saw off and hinge the neck of their bass,” she says.

Despite its mobility problems, Diana says the double bass is an essential instrument in orchestras, and in the past 20 years it has even forged its way as a solo instrument. “It is the only stringed instrument in a concert band, and it is so versatile — you can use it in chamber music, in a symphony orchestra, you can put gut strings on it to play early music, or you can use it in a jazz ensemble, or a big band.

In addition to her viola da gamba, recorders are Diana’s contingency plan for later retirement. “Recorders feature heavily in early music. They are a much maligned instrument,” she says and uncovers her collection of the woodwind instruments. “Look at this beautiful bass recorder. You can guess who is going to play that one when I can’t handle the double bass any longer — I just can’t stay away from the bass instruments!” she laughs.

Article by Jenny Walker

Highlife Vol.8 No.3 February/March 2004

| Site overview | |

| Harpsichords Australia Home Page |