Press GalleryCopyright © 2002 CBH & individual authors & photographers |

A secret hides inside the strings of the harpsichord, and Carey Beebe knows how to coax it out for everyone to hear.

He starts by thumping a metal tuning fork. The gentle hum of a perfect “A” gives root to his delicate task: adjusting the strings to restore a musical personality unfamiliar to the modern ear.

Beebe will repeat this effort over and over again during the Carmel Bach Festival. The 38-year-old harpsichord technician from Sydney, Australia, has been hired as chief caretaker of four keyboard instruments that will be used during the festival.

Beebe builds harpsichords and travels the world to maintain their health. He arrived in Carmel via Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Bombay, London, Paris, Boston, Toronto, Seattle, and Vancouver, B.C. After the Bach Festival he’ll spend a week in New Zealand before returning home.

ORVILLE MYERS |

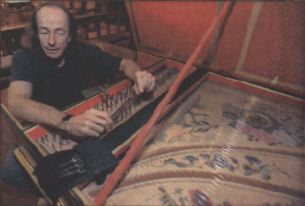

| Harpsichord technician Carey Beebe is

in town for the Bach Festival to care for four of the instruments, including this French-style harpsichord at All Saints Church in Carmel. |

“There’s very few people who can do this work,” said Beebe, by way of explaining the long trip. “Not all harpsichord makers have the equipment or the expertise to do something out in the world. It’s like a racing car: You can lovingly restore something, but until you put it to the test with the really top drivers, you don’t know how it’s going to perform.”

The strings of a harpsichord are plucked by quills, not struck by hammers like a piano.

It’s a nervous instrument, with a wooden soundboard only 3 millimeters thick, sensitive to slight shifts in the environment. Moving a harpsichord even a few feet can alter its tune. So can a summer fog or a drafty room.

For Beebe, the harpsichord’s difficulty is also its magic. He has devoted his life to mastering the tension of its strings and the pleasing resonance created by its intervals.

The Greek philosopher Pythagoras is credited with uncovering the mathematic underpinnings of music. He learned that harmony is governed by ratio, but the set-up isn’t quite perfect: If you tune in a series of perfect fifths, the B-sharp where you end is not the same pitch as the C where you began.

The difference is known as the Pythagorean comma — music’s version of the leap year.

Pianos today are usually tuned in “equal temperament,” with the difference split evenly among all 12 notes within an octave. The piano is never actually in tune, Beebe says, but instead, equally out of tune.

That’s why on a piano, F-sharp and G-flat are the same note.

But composers of medieval and baroque music had different schemes for dealing with the Pythagorean comma. In tuning a harpsichord, a musician must choose among them. Will that key be G-flat? Or F-sharp? Or E-sharp-sharp?

Historic temperaments set out patterns of squeezing intervals to achieve desired effects.

Each temperament gives music a different flavor — some keys are peaceful and pastoral; others restless or harsh. “Serious players want to rediscover that, because it puts a whole new perspective on the piece,” Beebe said.

For the listener, he said, it’s a new way to experience music, one that draws varied responses.

“For many people, it’s intangible. Other people would focus on the harsh keys. They might suddenly think, ‘That sounds out of tune.’”

But the early temperaments also add detail and piquancy to music, Beebe said, creates tension and resolution, and underlines its emotional themes.

“It’s like if you were shortsighted, and you went outside and looked at the tree, and said, ‘That’s a tree’. Then you went and put on your glasses and you saw that there are leaves on the tree.”

Musicians try to match harpsichords and temperaments to the piece being played. But early composers didn’t generally note tuning instructions, so today’s performers must make an educated guess, based on their knowledge of history and the composer’s body of work.

No one knows, for example, which tunings Bach preferred. He is said to have been a masterful harpsichord player, but never wrote tuning instructions for his compositions.

For the Bach Festival, Beebe has been making generous use of a temperament called “Vallotti,” named after an Italian theoretician. Half the notes are perfectly in tune, and half are squeezed.

As a boy, Beebe never imagined that he would some day grow up to be a jet-setting harpsichord builder and technician. “I wanted to be an airline pilot or a doctor.”

Still, he said, those early dreams were more or less realized — it’s just that his patients are harpsichords, not people, and he welcomes house calls.

Article by Sara Steffens

The Herald (Monterey County) July 17 1999

| Site overview | |

| Harpsichords Australia Home Page |